at the lowest limit. 300 families at the Sitio Capuso resettlement site in the city of Mabalacat have homes but are waiting for electricity and water connections and infrastructure to deal with flooding problems.

Read the last of two parts: Part 1: The story of two villages in Pampanga shows the key role of local governments in disaster relief.

Pampanga, Philippines – More than 300 families in Sitio Capuso, a resettlement site in Mangalit Village, Mabalacat City, did not receive assistance to repair a damaged home caused by high water levels and high winds during Super Typhoon Noru.

For three weeks now, the main local headquarters for emergency situations has been dripping, not wanting to take responsibility for providing assistance.

After CSWDO head Josie Tanglao said she was waiting for an official report on Sitio Capuso, Rappler tried 14 times to call CSWDO but received no response.

It has been more than a year since the first families arrived at the resettlement site after the Hausland Development Corporation (HLDC) relocated them from land under development, and they still have to fend for themselves in order to get electricity and drinking water.

Emerson Madayag, who arrived with the first settlers in March 2021, said they were supplied with electricity upon arrival. Although suitable facilities are available and residents are applying with the help of local governments, the process is slow.

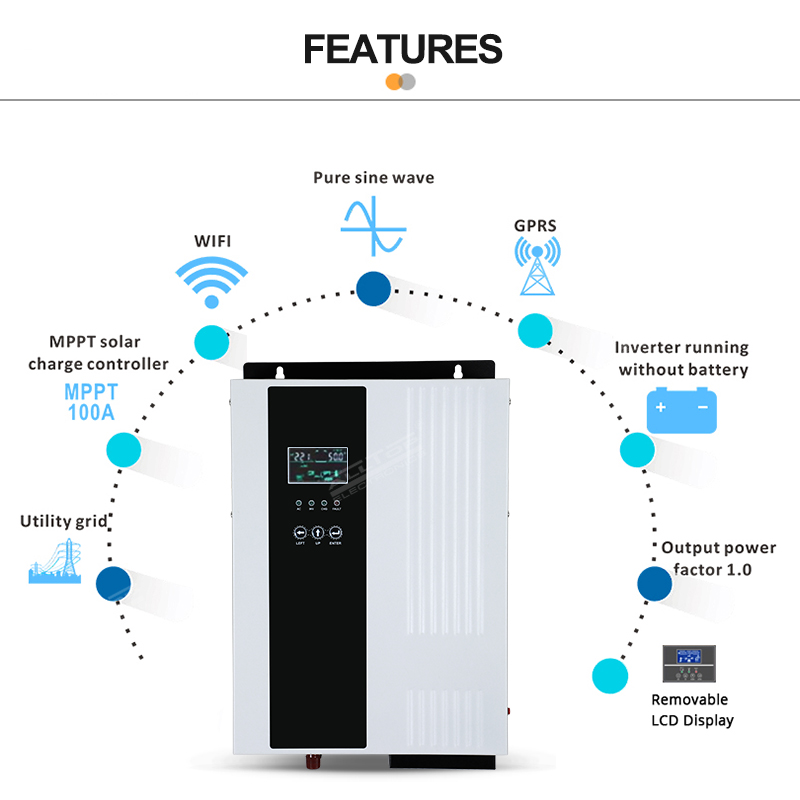

Some households buy cheap solar panels just to provide light for a few hours at night. Others, such as Rosalina Patombon, which will arrive in June 2022, use old motor batteries.

Another problem is the lack of running drinking water. 300 families do not know when they will stop using the two manual submersible pumps that serve the entire village.

Water from a deep well looks crystal clear through cheap filters bought from online stores.

For the poor trying to adjust to life on the outskirts of cities, the need to buy water is a huge burden.

Like other settlers of Sitio Capuso, Rosalina is involved in the waste and garbage trade, and also collects plastic, which is delivered by the kilo to the city of Angeles in exchange for rice.

Because they are now so far away from the centers that generate the most waste, their livelihoods have suffered since the resettlement.

The uneven road leading to the only access to Sitio Capuso also limited their mobility. From the village on foot 30 minutes to the main road, and then 20-30 minutes on a tricycle to the track.

A one-way tricycle ride from their village to the highway costs between 150 and 200 pesos. If they walk on the highway, they pay 35 pesos to ride a tricycle to the center of Mabalacata.

Rosalina sometimes works part-time around the house. But the nearly 400 pesos round trip wiped out nearly all of her income, and she often felt it was a losing battle.

The lack of power has also made it difficult to clean up after the flood, which occurs even during normal monsoon rains.

“The water is here and we’re scared because the quarry is nearby. Sometimes kids can’t get in because the water is so big and cars can’t get through because of the water,” Rosalina said. (We are worried about flooding because there are careers all around us. Sometimes children cannot go to school due to high water levels. Even cars cannot cope with flooding.)

HLDC attempted to implement a solution higher than the sandbag level recommended by the City’s Disaster Risk Reduction Office (CDRRMO).

“We provide drainage for the community leading to the Dolores River,” Amir Eizen, the company’s legal counsel, told Rappler.

“Unfortunately, due to mining, silt has accumulated in the drainage system we built. As a result, water flows through the settlement,” he said.

After Rappler inquired about the effects of flooding in Sitio Capuso, HDLC dispatched excavators on October 5 to clear the silt and “reactivate the existing drainage” by filling in the depressions near the village.

Private companies can provide land under informal settler resettlement laws. But basic utilities such as electricity and water, sewerage and road maintenance are the responsibility of local governments.

Rappler tried to contact the Mabalacat city council, but they did not respond to inquiries.

“However, any long-term solution will require the intervention of the LGU. The mission of the LGU is to promote general well-being and provide basic public services. In this case, especially when neighboring properties create problems for the community,” Ai Sen said.

The lawyer was referring to the large body of water behind Sitio Capuso, just across the border from Barangay Sapang Balen. During heavy rains, the ponds often overflow, and the water contaminated by quarry runoff ends up on the streets of the village.

In email correspondence, HDLC lawyers asked “our settlers to help us appeal and lobby the local government.”

“We are asking this because we firmly believe that Mabalacat LGU is very sensitive to the concerns of its citizens. Of course, we will work with LGU as a stable partner in the development of the city,” Ayon said.

But the people of Sitio Capuso said their requests for help during and immediately after Carding went unheeded.

Even with significant violations reported, CDRRMO and CSWD responses were null.

Rosalina stressed that the villagers are not idle people, but poor people who have stood their ground in the midst of huge obstacles to progress.

“A little difficult, but as they say, nothing is difficult if you work hard. Trade. Pick up some plastic,” she said. (It’s a hard life, but as they say, nothing is hard if you are persistent. That’s why we collect waste, we collect all kinds of plastic and we trade them.)

As a mother, Rosalina burst into tears when her children also began collecting rubbish to raise funds for school needs, as her income was barely enough to support her family.

“It’s so pathetic. But we’re holding on. I hope that our needs will also be met: electricity, water, materials for the house,” she said, waving her hand towards the roof, which they salvaged and put back together after Cardin blew it to pieces. Sincerely.

In the vast Clark Freeport area, upstream from the city of Angeles, Annalyne Ablon and her children struggle with other problems.

Under the leadership of Mayor Carmelo Lazatina Jr., their community of 27 families no longer feels left out. Their Sapangbato barangay has 500 families, many of them from Aeta.

They regularly receive government assistance. During a typhoon, local authorities contact them and help them move to a safer place.

Although the village has running water, the pressure can be so low that you have to bathe and wash yourself in a nearby stream.

Picking mountain bananas at a communal farm half an hour’s walk from the village brought the family 2,000 pesos. A harvested sack of camote (sweet potatoes) can be sold for 800 pesos, making an average of ten sacks per crop.

If they sell directly to the main market in Angeles City, they can earn 30-50% more. But since they don’t have vehicles or marketing tools, they are left to the mercy of middlemen.

Nevertheless, Analin and her husband were able to build their own home and raise a family of six while working to increase their income so their descendants would have access to education.

Her main concern is her children and the discrimination and ridicule they continue to face in the Lowlands.

“That’s why we send them to school so they can be exposed too. Because when the locals come to the plains, other people like you, number one, is real discrimination,” Analyn told Rappler on Sept. 29. (We make sure they go to school to be exposed. Because some people like you (meaning reporters) is the number one problem when tribesmen go to the plains is discrimination.)

The day Rappler visited Sitio Target, Analin said that one of her children had just arrived from a downtown mall.

“What did they do? Do you know the sound of monkeys? This is the sound they make when they see the locals,” said Aeta’s mother. (What do they do? Do you know what sounds monkeys make? When they notice people from our tribe, they imitate them.)

Aggressive Analin was not afraid to tell the questioner. She reminded them that the law makes it illegal to discriminate against them.

She also has no qualms about calling criminals idiots or telling students that their education will go to waste if they don’t learn to respect people who are different from them.

Analyn recalls how she advised a student to visit their community during a school immersion and took the liberty of calling them “balugs” and monkeys. She warned that if the elders heard abuse, the visitors might not get out alive.

“If they see that you are in pain, they will annoy you even more,” she said in Filipino. When we resisted, they were silent. – Rappler.com

high power solar panels,solar panels in winter,best roof for solar panels

https://www.alltoplighting.com/alltop-2022-complete-ongrid-1000w-3000w-5000w-7000w-solar-system-invertor-system-240v-1kw-3kw-5kw-7kw-solar-energy-systems-product/

Post time: Oct-17-2022